The daily Siddur has a long list of blessings for what are colloquially called “everyday miracles,” prodding us to be grateful for the sublime wonder of simply waking up in the morning. One of those blessings reads:

.בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה׳, אֱלֹהֵֽינוּ מֶֽלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, פּוֹקֵֽחַ עִוְרִים

Blessed are You, O G-d, ruling spirit of the universe,

who opens [the eyes of] blind people.

I say it every day, but I’m sure I’m not the first hearing-impaired person to wonder, why isn’t there a parallel prayer that reads:

.בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה׳ אֱלֹהֵֽינוּ מֶֽלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם מַשְׁמִיעַ חֵרְשִׁים

Blessed are You, O G-d, ruling spirit of the universe,

who allows deaf people to hear?

I don’t know the answer to that question. Perhaps it’s because deafness in ancient times was linked with cognitive disability (the heresh, or deaf-mute, in the Talmud is considered developmentally disabled and relinquishes some legal rights). Or maybe it’s because the word Sh’ma, “Hear,” means so much more than just the physical ability to hear; it means intellectual understanding as well.

Neither of those answers are satisfying, but they do make me wonder about the place of G-d in my own journey from hearing loss to restoration…

Almost exactly five years ago, in August 2019, I had cochlear implant surgery on my left ear, which gave me a new way of hearing and improved my quality of life in countless ways. I’ve often wondered how different my Covid pandemic experience would have been if I hadn’t had the surgery six months earlier; I’m sure the isolation and distancing would have made for a much lonelier experience.

On Thursday I’ll return to Mass Eye & Ear in Boston and have the surgery on my right ear. I have all of the appropriate trepidation that one has before a significant operation. But—knowing much better what to expect this time around—I’m very excited to be on the road to “bilateral hearing.”

The surgery is wondrous stuff, and even though I understand what will happen, the truth is I only understand it a little bit. There’s still an element of magic that takes place.

In essence, the surgery enables me to “hear without my ears.” The implants in my head, together with the external processors that I wear, will process electronic signals and send them directly to the audial parts of the brain. They literally bypass the ears, and the brain itself does all the heavy lifting to process sound. That’s what happens; but I still find it astonishing and rather miraculous—and despite all my reading up on the subject, I really can’t explain how the result is comprehensible sound.

What I do know is this: the cochlear implants have enabled me not only to function, but to flourish. Ever since hearing aids really stopped being sufficient for me—I am now just about totally deaf—the CI has enabled me to hear Heidi’s voice, to teach classes over Zoom, and to enjoy music again.

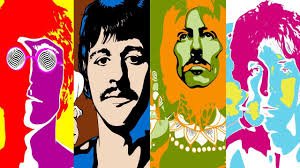

In the weeks ahead, all this will be enhanced for me. Not only has my hearing been restored, but I’m anticipating bilateral hearing, where finally my ears work work in synchronicity with each other. My first CI literally brought music back into my life; this second one… well, it will be like when the Beatles moved from the black-and-white mono of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and exploded into the stereo kaleidoscope of sound of Sgt. Pepper. (I don’t think I’m exaggerating here.) These things are just miraculous.

From this…

…to this.

I use that word miraculous purposefully but carefully. Miracle can be such a grandiose term. I think we all have a “miracle threshold,” where everyday wonder overflows into genuine spiritual astonishment. And the CIs definitely surpass my personal miracle threshold.

In his new and important book The Triumph of Life, my teacher Rabbi Yitz Greenberg makes some important and startling observations about miracles. Rabbi Greenberg suggests that, since the advent of modernity, we are living in the third great religious era of Jewish history. The First Era was the period of the Bible, which essentially ended two thousand years ago; and the Second Era saw the flourishing of Rabbinic-Talmudic Judaism, which extended through the end of medieval times.

In this Third Era, Rabbi Greenberg maintains, we live at a time of an amazing religious paradox. On one hand, G-d is more hidden than at any other time in human history. Yet, simultaneously, miracles are more abundant than ever! The wondrous medical advancements that have eradicated once-terrifying diseases (polio; smallpox) are only one illustration of the maturation of the human role in living in covenant with G-d. What makes them miracles is the synergistic partnership of divine inspiration and human ingenuity. In Rabbi Greenberg’s words:

In this moment, G-d becomes totally hidden, not to distance from humanity but to come closer… Henceforth, humans will execute the Divine interventions that rise to the level of miracles. G-d will be present and participating, but miracles will not represent changes of natural law by an “outside” or Divine mind. Rather, they will represent human actions and understandings of G-d-given nature that trigger remarkable outcomes, using natural phenomena and directing them consciously to needed results and cures. The miracles are inherent in the natural laws that govern the interactions of matter; humans will bring them out. (The Triumph of Life, p.185).

This is daring and radical theology. It will be on my mind on Thursday as I enter Mass Eye & Ear and in the days ahead as I recover from the operation.

I’m aware of the remarkable good fortune and privilege that I have to live in a time and place where surgery like this is available and affordable. (Although it’s spreading around the world. Through my rabbi, Joel Soffin, and the Jewish Helping Hands organization, I’ve recently been in touch with a young man in Rwanda who is the recipient of a cochlear implant.) That only deepens my sense of awe and wonder—wonder for the unfathomable intricacy of adaptability of the human brain; for my surgeon, nurses, and audiologists; for my family and friends and their caregiving and support. And with the wonder—also the determination to respond with gratitude and thanks.