The official release of Bob Dylan’s “Gospel Shows” is bringing a lot of people back to a time when, for them, the ‘60s counterculture really died. Here was Dylan—Hebrew name, Shabtai Zissel ben Avraham—singing songs of born again Christian faith, the glories of being saved by Christ, and condemning the unbelievers of Sodom. From 1979-1981 he released a triptych of albums of these songs—Slow Train Coming, Saved, and Shot of Love—and, starting in November 1979, would only perform songs in concert that reflected his newfound covenant with God. In so doing, a lot of old fans ran for the hills.

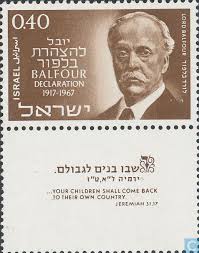

Dylan—that is, Robert Alan Zimmerman—had a Jewish upbringing in Hibbing, Minnesota. His parents were American-born children of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. He trained for his bar mitzvah with Rabbi Reuben Maier in the rabbi’s apartment above a local café (his father later related that Bob showed great proficiency with Hebrew). He attended Camp Herzl, a Jewish and Zionist summer camp in Wisconsin, during his teen years.

The release of these Gospel Shows (and it’s momentous; I’ve been waiting for the so-called “Bootleg Series” to get around to this era) raises again questions that dogged music fans back then: What happened to America’s greatest songwriter in the late ‘70s? How could Jewish fans listen? And as for these songs of heavenly salvation—what the hell?

I’ll offer one fan’s interpretation. I’ve never met Bob Dylan, so I may be way off base. But I’ve read many biographies and interviews of the man, and more importantly, I’ve tried to pay close attention to every note of his recorded oeuvre (and many bootlegs, which are essential for understanding Dylan’s art).

Dylan himself can be hard to trust when it comes talking about himself or his music. While there are many pearls in his autobiography Chronicles, some reviewers noted that he totally avoided writing about the moments that most people would actually be interested in. In the ‘60s, his press conferences were a hoot—because most journalists were totally clueless about his efforts to bring poetry and art to popular music, he messed with them:

Interviewer: What is your real message?

Bob Dylan: My real message? Keep a good head and always carry a light bulb.

He tends to speak in parables, especially when he’s feeling like a trapped animal. I imagine he felt that way through much of the ‘60s, but it persisted in the subsequent decades. For instance, in 1991 he was presented with a Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement. I suspect that Dylan recognized the Grammys for what they were: hollow trophies given out by self-congratulatory ghouls from the music business, and “lifetime achievement” is even worse—what they give you when they acknowledge that your relevance is long past, and that if you’d just hurry up and die they can start reshaping your legacy to fit their own preconceptions. So Dylan—50 years old—slithered to the podium and virtually spoke in tongues, as far as the corporate throng was concerned.

Well, um… uh, yeah. Well my daddy, he didn’t leave me too much. My daddy once said to me… [looooooong uncomfortable pause. Nervous laughter from everyone. Security puts their hands on their holsters.] Well he said so many things, y’know? [laughter]

He said, son, it is possible for you to become so defiled in this world that your own mother and father will abandon you. And if that happens, God will always believe in your own ability to mend your own ways. Thank you.

Add to his list of accomplishments: the best awards speech ever.

But in that speech (and its allusion to Psalm 27:10), which is a total fiction (Abe Zimmerman said no such thing) and a dodge (please get me off this godforsaken stage), there is also a great reveal: a desperate statement from a man “so defiled” who has been to hell and back, including the depths of alcoholism. And who believes in salvation—but only from an external force, a rock of ages.

II. Apikoros

To understand Dylan’s gospel years, one has to understand that he has never been halfhearted with his art. When he commits to a guise, he dives in completely. I believe that Dylan was a true believer during these years. It proved short-lived and eventually he resumed performing non-Christian-themed songs (“Thank God,” said many old fans), but from 1979-1981 he was sincere in his devotion.

I sense that Dylan has a streak in him that makes him say, “You think you can put me in a box? Why should I be what you want me to be?” I find this orneriness to be very appealing—perhaps because I have some of it myself. He devotes a lot of space in Chronicles to spitting with disgust when people tried to call him the “Voice of the Generation” of the ‘60’s. Who in hell, he asks, would want to be anyone’s “voice of the generation”? For a long time he was publicly putting down people who would pin a label on him—surely that’s what “Ballad of a Thin Man” and “Positively Fourth Street” (“You’ve got a lot of nerve / to say you are my friend…”) are about? And in case there was any doubt, there was “Idiot Wind,” the most vicious put-down song ever:

Even you, yesterday, you had to ask me where it was at

I couldn’t believe, after all these years, you didn’t know me better than that, sweet lady

A recap of Dylan’s career shows this bait-and-switch. He’d adopt a certain style, and throw himself into it completely. He’d write such compelling music in that mode that fans would hop on board. Then, abruptly, he would discard that mode for another one… enraging those who thought they had embraced the “real Dylan.”

In Judaism, this is called being an apikoros—as close a word to “heretic” that we have. But we have a funny relationship with our apikorsim. Some of them are some of the most important Jews in history.

So in 1961 he shows up in New York completely enamored with Woody Guthrie’s Americana: work shirt, acoustic guitar, and hokey humor (to make sophisticated points about the human condition) intact. From there was an evolution to the coffee houses of Greenwich Village, hanging with Joan Baez and Dave van Ronk, and singing at the 1963 March on Washington for Martin Luther King.

The insular folk scene was so self-righteous and cocksure that to leave it was an act of blasphemy. So when Dylan showed up at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival with a raucous electric band, whomping out songs of surreal poetry, the self-appointed gatekeepers revolted. Pete Seeger tried to cut the electric cords with an ax. Peter Yarrow, the distressed master of ceremonies, tried to nudge “Bobby” back out for an encore… “This time with an acoustic guitar.”

That’s what Dylan left behind when he started his barnburning world tour of 1966 with his electric band The Hawks. But the folkies wouldn’t let it go. Some fans embraced this loud electric rock, but the old timers booed, and slow-clapped between songs. The zenith was in Manchester, England, when, just before the band tore into “Like a Rolling Stone,” a distressed old folkie had enough. “Judas!” he howled at the Jew standing on stage.

But the heckler was already a fossil. Dylan had recorded three electric albums that made him a hero to new rock counterculture. And we know what Dylan thinks about heroes, right?

So he retreated. After touring the world as one of the biggest and loudest rock acts… he shut up, and disappeared for 1967 and its hallucinatory Summer of Love. When he emerged, it was in a new guise: Country Bob, singing on the Johnny Cash show, and recording with Nashville session pros. Gone were the amphetamine screeds of 1965. And the counterculture was pissed. In 1971 Dylan released Self Portrait, two records of country songs and covers, and Greil Marcus opened his famous review of the album in Rolling Stone with the words, “What is this shit?”

Country music at the turn of the ‘70s was not the sterile commodity that it would become. It represented the antithesis of the ‘60s counterculture; the enemy of the hippies and all they stood for. Again, Dylan had adopted the pose of the heretic. He was saying, again, to his fans: You really want to follow me? Well, let’s see if you’ll follow me here…

For all its integrity, this does show a rather perverse relationship with his audience, to say the least.

In the mid-70s, his star was ascendant again. He reunited with The Band, and through 1974 performed the highest-grossing rock tour of all time. He made hugely well-received albums that reflected his mastery of the ‘70s singer-songwriter convention. By 1978 was performing a 115-date world tour with a big band, full of horns and back-up singers.

But his was a tormented soul, and it was time for another sharp turn.

III. Dylan & Religion

One other thing before we approach the Gospel Years. Religion—the Bible, specifically—has always been part of Dylan’s neshama. Christopher Ricks has written an excruciating treatise on this, but I can add one or two points minus all his exegesis.

Dylan knows the Bible backwards and forwards; it pops up when you least expect it. There are moments like the “slain by a cane/Cain” line in “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” for instance. But—hands up—how many people know the title of “Rainy Day Women Nos. 12 & 35” (“everybody must get stoned!”) comes from Proverbs 27:15?

An endless dripping on a rainy day

And a contentious wife are alike

But I like to think that even in his early days, Dylan was attracted to the Old-Time Religion of America, the kind that includes periodic Great Awakenings and embraces Jonathan “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” Edwards, Jefferson’s Bible, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Dorothy Day, and the apocalpyticism of bluesman Blind Willie Johnson. These were all forms of a distinctly American faith.

Even a Jew like Dylan—even a Jew like me—can love Woody Guthrie’s version of Jesus Christ. For Woody, this was the true Jesus:

Jesus Christ was a man that traveled through the land

A hard working man and brave

He said to the rich, "Give your money to the poor,"

So they laid Jesus Christ in his grave.

And:

This song was made in New York City

Of rich men and preachers and slaves

If Jesus was to preach like he preached in Galilee

They would lay Jesus Christ in his grave.

Amen, selah, and tell me that those lines aren’t even more prophetic in Trump’s America than they were back in Woody’s dust bowl days?

It’s not hard to imagine a young Dylan absorbing the lessons, and assimilating them into the work.

IV. Saved

With that background, I think there are three parts to understanding Dylan’s embrace of a born-again Christianity in 1979.

First: As we’ve seen, it follows his pattern. When his fan base becomes enormous, he suddenly takes a sharp turn, shaking off fans who feel “betrayed” by his “heretical” embrace of something new, often the polar opposite of where he’s been.

Second: Dylan is a polyglot of American music. He’s been an authentic purveyor of Woody Guthriesque Americana, protest folk, delta blues, electric rock, straight-up country, bluegrass, and, since 2011, jazz standards and the Great American Songbook. Since he’s embraced virtually every indigenous form of American music, it would be strange if he didn’t explore gospel music.

And when he explores something, he gets completely immersed in it. (In 2003 he wrote the song “’Cross the Green Mountain” for the Civil War movie Gods and Generals. They say he spent days in the New York Public Library researching the Civil War to get the lyrics just right.)

Third: None of this is to say that his religious conversion, even though it was short-lived, wasn’t authentic. I believe that he believed.

With an increasingly jaundiced eye he surveyed the music business of the ‘70s. Drugs and decadence were everywhere. He’d been living this life for a while. And he was living in Malibu, where friends and acquaintances were receding into their own chemical hells (see under: The Band).

Furthermore, his marriage to Sara Lowndes had collapsed. They had been together since the ‘60s, and with Sara he had five kids and fled the turbulent “Judas!” years to a farmhouse in Woodstock. He wrote love songs to their family on New Morning, grieved their break-up on Blood on the Tracks, celebrated their reconciliation on Desire and its song “Sara,” and ultimately the whole thing went south.

So picture the man’s state of mind: exhausted, divorced, cynical, burnt-out.

The story goes that several of his backing musicians were already born again, and his interest was piqued by their religious discipline during the ’78 tour. And then there’s this incident from the end of the tour, San Diego, November 17, 1979:

Towards the end of the show someone out in the crowd… knew I wasn’t feeling too well. I think they could see that. And they threw a silver cross on the stage. Now usually I don’t pick things up in front of the stage. Once in a while I do. Sometimes I don’t. But I looked down at that cross. I said, “I gotta pick that up.” So I picked up the cross and I put it in my pocket… And I brought it backstage and I brought it with me to the next town, which was out in Arizona… I was feeling even worse than I’d felt when I was in San Diego. I said, “Well, I need something tonight.” I didn’t know what it was. I was used to all kinds of things. I said, “I need something tonight that I didn’t have before.” And I looked in my pocket and I had this cross.[1]

At 38 years old, Shabtai Zissel met Jesus.

V. The Music

So what about the music?