…but sometimes it’s better to be smart than right.

The Trump administration’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital is a cynical political maneuver—but there are plenty of good, historical reasons why Jews may feel torn. Here’s my attempt to sort through the issues and to explain why something that should seem obvious on one hand is so profoundly disturbing on the other.

Plenty of people may find themselves saying, “Isn’t Jerusalem already Israel’s capital?” And of course it is. All of Israel’s government offices are in Jerusalem, Israel’s largest city. So, too, are the Knesset and the Supreme Court. So is Hebrew University, the national university of Israel, founded in 1918. The office of the Chief Rabbinate, a reprehensible institution but a significant national one nonetheless, is likewise in Jerusalem.

Furthermore, spiritually speaking, there has never been any doubt in the Jewish mind about Jerusalem's status. Since the days of King David some 3,000 years ago, Jerusalem has been the earthly capital of Jewish worship. Of no other city did the Psalmist cry:

If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither

Let my tongue cleave to my palate if I cease to think of you,

If I do not keep Jerusalem in mind even at my happiest hour. (Ps. 137:5-6)

For the Jewish soul, Jerusalem is home.

In a perfect world—of course the U.S. embassy should be in Jerusalem, the only capital of Israel.

So what’s the controversy?

When the United Nations in November 1947 voted to partition British Mandate Palestine into two states, a Jewish one and an Arab one, Jerusalem was considered too contested; it was to be internationalized. After the 33-13 U.N. vote passed, the Zionists accepted the plan and the Arab nations rejected it. (There were some enraged voices, especially from far-right nationalist corners of the Zionist movement, to reject the U.N. plan on the grounds that there could be no Jewish state without Jerusalem as its capital. David Ben Gurion sagely chose otherwise.)

When Ben Gurion and the Zionist leaders signed Israel’s Declaration of Independence on May 14, 1948, it was an endorsement of the U.N. plan—the Declaration was signed in Tel Aviv, and the understanding was that Jerusalem would, indeed, be internationalized.

But the U.N.’s proposed boundaries never came to fruition. Within hours of Israel’s independence, she was attacked simultaneously by the surrounding Arab nations. When an armistice was reached the following year, Israel’s precipitous borders were somewhat expanded—and a foothold was established in Jerusalem, a lifeline to the thousands of Jews who lived there (and who were isolated, endangered, and on a few occasions, massacred during the War of Independence). Jerusalem was a divided city: the Old City and eastern neighborhoods of Jerusalem were under Jordanian rule; the western part of the city was Israeli. Into those western neighborhoods, the apparatus of the government moved.

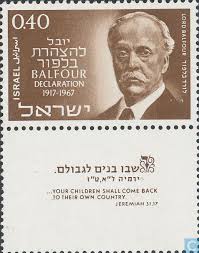

After Israel’s stunning victory in the Six Day War in 1967, all of Jerusalem came under Israeli control. While the Muslim holy sites were handed over to the waqf—the Jordanian-controlled Islamic religious authority—both East and West Jerusalem became one Israeli municipality. Everywhere in the Jewish world, souls were stirred. The new anthem of the Jewish people became Naomi Shemer's Yerushalayim shel Zahav / "Jerusalem of Gold."

But for most of the nations of the world, including the U.S., Jerusalem never gained its status as Israel’s capital, because they continued to cling to the 1947 U.N. Resolution 181 rather than comprehending that the status quo had irrevocably changed. 70 years later, that’s still the case.

The problem is precisely this: everything about Jerusalem causes passions to be inflamed. Even though many Jewish residents of the city have never stepped foot in the Palestinian neighborhoods such as Beit Safafa, Silwan, or Shuafat, there is a strong sense that Jerusalem can “never be divided again.” And for Palestinians, Jerusalem is the inevitable capital of their state-in-waiting.

So there are threats. Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas has indicated that if the Trump Administration makes this move, it will pull the plug from the barely-on-life-support peace process. Worse, the implied threat is that the Palestinian street will go ballistic, launching, G-d forbid, a Third Intifada and new wave of violence and terror. That violence could easily spread beyond Israel.

On one hand, some supporters of Israel will understandably say—why should we allow the threat of terror to stop us from pursuing a goal that is ultimately right? Why would we cave in to that sort of blackmail?

But on the other hand—often it is better to be smart than to be right. What, really, is to be gained by this move, besides a sense of historic injustice corrected?

The danger of this spiraling out of control is real. No one’s life would be changed or improved by this symbolic U.S. recognition—but a lot of people’s lives could be devastated by the eruption of tensions. That is why one pro-Israel U.S. administration after another—Republican and Democrat alike—has put off making such a move as this. (I suspect that behind the scenes, the Israelis were nodding in assent. You really don’t hear about the Israelis making a big deal that U.S. embassy is not in Jerusalem—and for good reason.)

As scholar Micah Goodman has written in his important book Catch-67, the United States could be using its power to ease tension between Israelis and Palestinians, taking short-term incremental steps to build trust (rather than trying to force final stages of a peace process at this time). His book—a bestseller in Israel—offers concrete examples steps about how to do just that.

We should question the timing of this move: Does it have anything to do with distracting attention from Donald Trump’s growing panic over the Justice Department investigation of possible collusion with Russia? Or with the increasing momentum in Israel of corruption charges against Prime Minister Netanyahu? And in a time of great tension between Israel and American Jews, over the Western Wall and pluralism issues in general, doesn’t the timing seem just a little self-serving for these politicians?

Whether or not the announcement is self-serving for the embattled politicos, all of us should pause to think about whether we want to be smart or right at this particular juncture.

The Talmud (Sanhedrin 93b) maintains that one aspect of King David’s leadership was that he was mavin davar mitoch davar: that he could anticipate how one thing causally leads to another. Thoughtful leaders should know that their actions have consequences, both intended and unintended.

That is what this moment calls for. Sadly, tragically, we are not currently blessed with leaders who have this sense of foresight.